Personal Status issues - those dealing with matters under the umbrella of family law, including marriage, divorce, child custody, adoption, and inheritance - have been the focus of some of the most contentious debates over the role of Islamic law in post-Saddam Iraq.

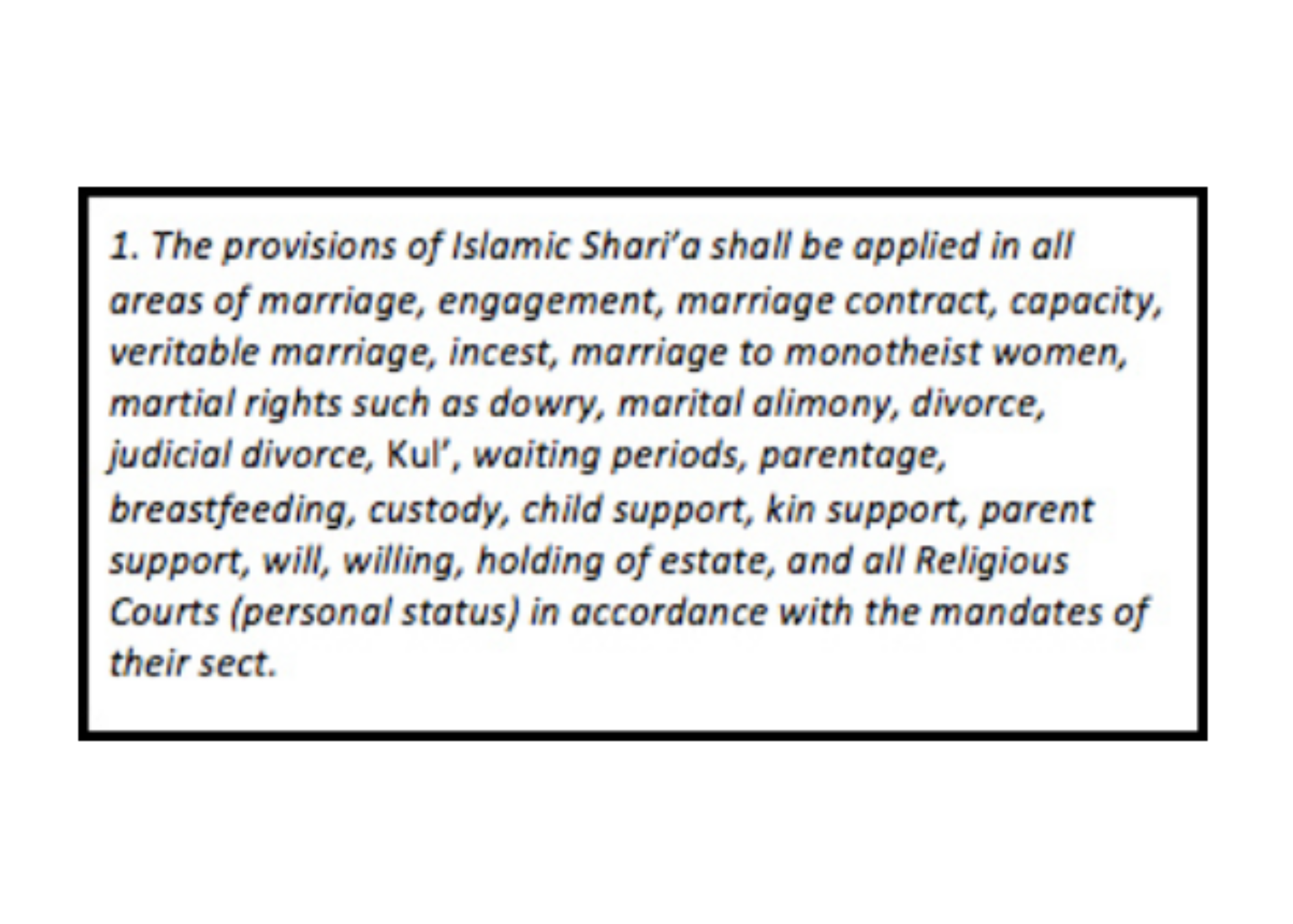

While strict Shari’a guidelines may fall to the wayside in other realms of litigation, in the areas of family law and personal status - those which most directly affect Iraqi citizens - religious authorities have made clear their intent to uphold, to the best of their ability, the principles of Shari'a.

At the center of controversy has been the Iraqi Personal Status Code, Law 188, which dictates the way in which family law issues are dealt with. Instituted in 1959 by Iraq’s left-leaning revolutionary government at the time, the code was a unified, codified national law that treated all Iraqi citizens as equal regardless of their sectarian affiliations.

The law replaced the former system of differential treatment of Shi'ite and Sunni Muslims and other religious minorities under separate Personal Status courts whose judges decided cases based on their own religious training (Al-Ali, & Pratt). These courts became a branch of Iraq’s regular court system, and it was the judges’ role to implement the codified law rather than interpret Islamic law on their own.

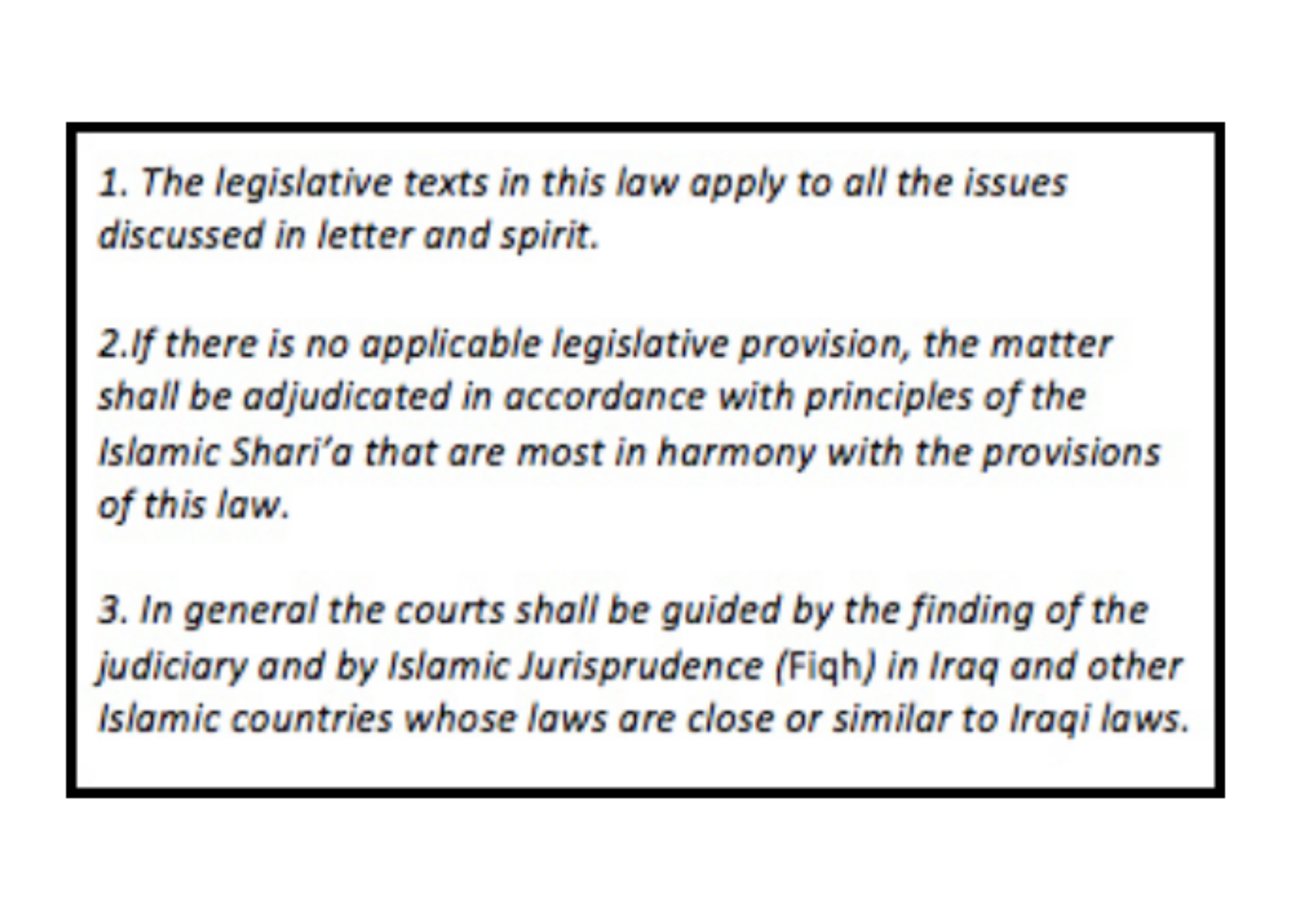

The law stipulated that judges could refer to Shari'a principles only when the codified text failed to offer a provision for a certain situation (Brown, 2005). The code is based on French civil law as well as Sunni and Jafari (Shi'ite) interpretations of Shari’a, forming what some consider a successful model of a civil code compatible with Western law that is rooted in Shari'a (Stigall, 2006).

The code, though, is based on many central rulings of Shari'a disadvantageous to women: polygamy, for instance, is allowed as long as it is approved by a judge; men have greater power to initiate divorce, and can divorce their wives simply by pronouncing "three repudiations"; all divorces, for that matter, must be filed with a Shari’a court; inheritance laws lean in favor of men, awarding female heirs half of what their male counterparts would are entitled to by law(American Bar Association, Iraq Legal Development Project, 2007).

Since the code's stipulations must fall within the "legitimate interpretations of Islam, there are technically no civil marriages" (Brown, 2005). However, since all Muslim marriages, including inter-sectarian ones between Sunnis and Shi'ites, fall under its unified Islamic jurisdiction, one could argue that the law does allow for civil marriages via such non-traditional unions.

Intermarriages between Sunnis and Shi’ites are in fact frequent, comprising one-third of all Iraqi marriages prior to 2003. These rates have dropped significantly, though, as violence has increased. Mixed couples risk violent attacks, forced separation or both at the hands of Islamic militias.

A surprising government-sponsored program in 2009 initiated by Iraqi Vice-president Tariq al-Hashemi offered monetary incentives to couples who intermarried (Fadaam & Madhani, 2009). The program’s stated aim was to ease sectarian tensions, and though it raised eyebrows, the program flourished despite potential consequences for personal safety.

Inter-religious marriages, however, are less common. Marriages between Muslim men and Christian women are permitted and treated like other Muslim unions. Muslim women, however, are forbidden from marrying outside their faith.

Non-Muslim couples, other the other hand, are dealt with by a multi-code system where marriage issues are covered by secular elements of the Personal Status Code and respective religious authorities (UNHRC, 2005).

So while the Iraq’s codified personal law is not secular in nature, it weakens the power of religious establishments by removing their ability to interpret law independently of the state, or to oversee their own personal status courts (Brown, 2005).

The law, which had been in place under Saddam Hussein, was thus viewed by many as an extension of his discriminatory policies against religious Shi’ites, and like so many policies under his regime, as sacrificing "sectarian principles on the altar of national unity" (Stigall, 2006).

Not surprisingly, attempts to overturn it came shortly after Saddam was removed from power in 2003. Abdul Aziz al-Hakim, then leader of the Supreme Council for Islamic Revolution in Iraq (SCIRI), proposed Resolution 137 the same year, reinstating a system in which legal cases relating to family law would be handled in either Sunni or Shi’ite Shari’a courts and presided by Islamic jurists rather than state judges.

The resolution would in essence overturn Iraq’s Personal Status Code and enable religious leaders to rule in family law cases (American Bar Association, IRLDP, 2007).

Opposition to it brought together women’s groups in and outside of Iraq and gave momentum to what would become a growing Iraqi women’s rights movement. Their outspoken resistance, along with that of secularists, Kurds, and especially, hundreds of unaffiliated individuals who protested publicly against what they the saw as the erosion of Iraqi civil rights, resulted in the ultimate repeal of Resolution 137 (Usher, 2004).

Though the campaign was a success, it had represented a Catch 22 for women: the code they were defending, though relatively progressive compared to other countries in the Middle East, still allowed for blatant mistreatment of women under the legal system at large. Iraqi criminal code, for example, imposes punishment for any sexual relations outside marriage (Edward, 2009).

These include fines and detention, but can be decreased or removed if unmarried participants end up marrying. According to the Organization for Women’s Freedom in Iraq, the law has led to female victims of rape marrying their male predators in order to escape a prison sentence (Mohammad, 2011).

Thus, women were left essentially where they had begun before the battle against Resolution 137, with a 1959 Personal Status Code based in Shari’a law, which still blatantly discriminated against them in many instances.